(2024) “Stopping Firestone and Starting a Citizen ‘Revolution from Below’: Reflections on the Enduring Exploitation of Liberian Land and Labour.” Third World Quarterly 45(1): 61-78.

Liberia Has Suffered 20 Years of ‘Negative Peace’. It’s Time for Change (Al Jazeera English)→

/On a typical weekday at St Peter’s Lutheran Church in Monrovia, children can be seen scoring three-pointers at the basketball court while adults crank up their engines in an adjacent parking lot. Yet, beneath the thick slab of asphalt on the church’s one-acre compound lie mass graves flanked by two large memorial stars painted in white.

On July 29 and 30, 1990 – as Liberia’s first war was raging – about 600 men, women and children were massacred in and around the perimeters of St Peter’s. Today their families and massacre survivors are embroiled in a battle of wills with the church over whether the erection of a basketball court and parking lot on mass graves demeans the victims buried there. The Lutheran Church Massacre Survivors Association (LUMASA) has also advocated for exhuming the remains and reburying them in a more dignified location.

As Liberia marks two decades since the end of its second war, which combined with the first took the lives of more than 250,000 people, the St Peter’s Church reckoning over memorialisation reflects the unfinished business of postwar stability and the country’s struggles with collective amnesia.

Since the conflicts ended on August 18, 2003, Liberia has only seen what the late peace studies pioneer Johan Galtung called “negative peace” – the absence of direct physical violence characterised by fears of relapse into warfare. Its transition from war to peace remains incomplete because its norms, rules and regulations continue to fuel inequality and injustice.

What Liberia should strive for is “positive peace”, which involves building values, customs and institutions that create and sustain peaceful societies…

Development, (Dual) Citizenship and Its Discontents in Africa (Cambridge University Press)→

/(2022) Development, (Dual) Citizenship and Its Discontents in Africa: The Political Economy of Belonging to Liberia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Paperback]

Race in/and Development (Routledge)→

/(2021) “Race in/and Development” in Henry Veltmeyer and Paul Bowles (eds.) The Essential Guide to Critical Development Studies (2nd edition). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge: 31-39.

The Political Economy of UK-Mandated Quarantine (African Arguments)→

/UK travel rules are another example of Northern hegemons’ disingenuousness on Covid.

Anyone who has survived British government-mandated quarantine after returning from a so-called “red list” country will admit the same thing: it’s the pits.

People have likened the experience to incarceration, but while convicts’ civil liberties are severely curtailed because they break what we might deem a social contract, the only “crime” people like me have committed is that we remain at the receiving end of a geopolitical race to the bottom. From refusing to grant South Africa and India intellectual property waivers to manufacture affordable Covid-19 jabs to hoarding vaccines, hegemons of the so-called Global North continue to play a disingenuous game of might makes right.

The UK’s travel rules are another example. Under the pretext of safeguarding public health, the UK has conjured up a scam that enables it to recover Covid-era financial losses. It does this while stigmatising countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America and extorting money from their citizens on a massive scale. Britain responded to international censure by “simplifying” its indefensible traffic light system beginning yesterday, but my experience in quarantine demonstrates why its red list must be completely eliminated.

Development, (Dual) Citizenship and Its Discontents in Africa (Cambridge University Press)→

/(2021) Development, (Dual) Citizenship and Its Discontents in Africa: The Political Economy of Belonging to Liberia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Hardback]

Liberia's Weah Might Be in for a Rude Awakening at the Polls (Al Jazeera English)→

/In a confusing about-face last month, Liberia’s Supreme Court undermined its own ruling that a controversial referendum, scheduled for December 8 alongside the nation-wide legislative elections, is unconstitutional.

Instead of explicitly cancelling the referendum, as most Liberian opposition parties and civil society actors have urged for weeks, the Supreme Court recommended instead that the eight propositions under consideration should be printed clearly in an Official Gazette and on ballots enabling the electorate to vote for or against each separately and independently.

This has buoyed footballer-turned-president George Oppong Weah, whose administration is using the referendum as a pretext to implement sweeping constitutional changes that may open up a small window for him to seek an illegitimate third term in office.

If Weah proceeds as speculated, he would be taking a page from the playbook of Alassane Ouattara of Ivory Coast and Alpha Condé of Guinea, whose successful third-term presidential bids earlier this year happened amid an opposition boycott, nation-wide protests and violent clashes with police. Ouattara insisted that a constitutional change in 2016 meant his very first term did not count towards a two-term limit; Condé reasoned that a constitutional referendum held a few months before elections enabled him to seek a third term.

While the Ivorian and Guinean presidents may have succeeded in their political coups, Weah may be in for a rude awakening. Regardless of whether an actual referendum takes place, Liberia’s polls next week will be a symbolic referendum on the once-popular, now embattled, president.

The US Government Kills Black People with Impunity Both at Home and Abroad (The Nation)→

/In early February of this year, 18-year-old Nurto Kusow Omar Abukar was blown to smithereens by American air strikes as she sat down for dinner with her family in Jilib, Somalia. Hurled indiscriminately by the US Africa Command (Africom) in its hunt for al-Shabaab militants, the bombs also injured Abukar’s younger sisters Fatuma, age 12, and Adey, age 7, as well as their 70-year-old grandmother, Khadija Mohamed Gedow. A few weeks later, on February 24, Africom lobbed a Hellfire missile that killed 53-year-old banana farmer Mohamud Salad Mohamud in the nearby village of Kumbareere.

As the murders of Abukar and Mohamud tragically demonstrate, the US military has inflicted some of the most grotesque forms of violence on Africans under the pretext of protecting Americans. According to Amnesty International, the United States has conducted over 170 aerial raids since 2017, triple the number of the previous three years, killing between 900 and 1,000 Somalis. And while there has been almost no public uproar about black African civilian casualties of America’s War on Terrorism abroad, they parallel black civilian casualties of domestic law enforcement at home…

Africa Does Not Need Saving During This Pandemic (Al Jazeera English)→

/It was inevitable that racism would rear its ugly head.

Having previously documented the long and shameful history of unethical drug testing on communities of colour across the globe, I was not surprised earlier this month when two French doctors proclaimed on national television that Africa would be the most appropriate location for a coronavirus vaccine trial. Never mind that this continent has the lowest recorded number of cases regionally.

For bigots who operate under the appalling assumption that black, brown, and other non-white bodies are easily expendable during times of crisis, COVID-19 presents the perfect storm. Yet, instead of expending energy on denouncing the doctors' asinine comments, as so many have already done, we should be reflecting on what Africa and other regions of the so-called Global South have to teach the world in this collective moment of reckoning.

‘We Don’t Know Who Be Who’: Post-party Politics, Forum Shopping and Liberia’s 2017 Elections (Democratization)→

/(2020) “‘We Don’t Know Who Be Who’: Post-party Politics, Forum Shopping and Liberia’s 2017 Elections.” Democratization 27 (5): 758-776.

This Is Our Country (Warscapes)→

/

I feel like an imposter. Out of place and exposed.

Monsoon-like rains have subsided and the dry season air is thick and balmy in Monrovia, Liberia. It is circa October 2007. I am 25 and ‘home’ for the first extended period of time since international headlines stopped calling our country’s 14-year armed conflict ‘brutal’ and ‘grotesque’. Since our former head-of-state-turned-regional-warmonger was exiled.

During an earlier Christmas-season visit in 2002, I embrace this land of my birth, its people and their idiosyncrasies with a fierceness that throbs. It is the first of first returns since leaving, aged six, to join Mom and Dad in Washington, DC. There is a lull in the heavy fighting but I can count on fingers and toes war-era checkpoints that partition the bumpy Roberts International Airport road, a two-lane winding expanse surrounded by lush forest.

I marvel at daylight tours of our shell-shocked capital city and its suburbs, of bullet-ridden concrete fences, sprawling estates, open-air markets, beaches that beckon. Some of the sites unlock blissful memories of my tree-climbing and Knockfoot-playing girlhood. Others reveal visible and psychic wounds, like the crumbling edifice of a maternal uncle’s home, or the gaping hole left by a paternal grandfather whose disappearance at sea in the 1960s we attribute to the occult.

Under a star-lit sky, I greedily gulp down family tragedies and triumphs narrated late into the night. These are fevered attempts to fill in the gaps of lives separated by time, space and place. By war and peace.

Violence, of both the physical and structural kind, has numbed our senses. This leaves me circumspect. Macro-level talk is too dicey, so I try to speak solely about the familiar and familial. While Mom has given her blessing for me to be here on the condition that I keep all political views to myself, Dad is more supportive of my need to wrestle with our complicated country. He does not begrudge me for squandering all my savings on a roundtrip flight from Accra to Monrovia, purchased before notifying both parents because I know they will disapprove. A four-month stint studying at the University of Ghana becomes the perfect decoy for plotting my prodigal return home, and Dad admits that he considers my actions plucky.

Yet, despite a steely facade, I am far from brave five years later. My wishbone-shaped legs wobble in black mini-pumps—a parting gift from my mother—as they emit a shiny glow of newness. Though quick to shrug off others’ opinions of me, more out of insecurity than confidence, I know that we Liberians have mastered the art of judging a book by its cover. The content of one’s character is of less significance, so my mother spends much of my childhood, adolescence and young adulthood playing ‘respectability police’. She tries to exorcise my wilfulness, inherited from a lineage of Kru warriors who once battled black migrant settlers attempting to carve out a ‘land of liberty’, now Liberia, that did not belong to them. Back then, I resisted Mom’s impulse to shield me from razor-sharp scrutiny that is gendered, aged and classed.

Her armour of protection now gone, I feel naked. In an effort to smooth out any seemingly rough edges, lest I be harangued for them, I twist my shoulder-length dreadlocks with dark-brown tips tighter than usual at the roots.

De-centring the 'White Gaze' of Development (Development and Change)→

/(2020) “De-centring the ‘White Gaze’ of Development.” Development and Change 51 (3): 729-745.

How to Truly Decolonise the Study of Africa (Al Jazeera English)→

/From Cape Town to Cairo, Bahia to Bombay, recent calls to "decolonise the university" have gained traction across the globe. These demands correctly challenge the legacies of colonialism and attempt to subvert them in institutional structures of higher learning.

But the problem with this 21st-century "scholarly decolonial turn" is that it remains largely detached from the day-to-day dilemmas of people in formerly colonised spaces and places. Many academics mistakenly maintain that by screaming "decolonise X" or "decolonise Y" ad nauseam, they will miraculously metamorphose into progressive agents of change.

Some tragically believe that by ignoring leading thinkers who were "decolonising" long before it became a fad - including Edward Wilmot Blyden of Liberia and WEB DuBois of the US who were prominent as early as the mid-to-late 1800s - they can carve out "decolonisation" as their scholarly fiefdoms.

Still others erroneously contend that "decolonial" street credibility can be acquired by simply adding non-whites to their reading lists, journal editorial boards, speaking panels, research collaborations, book contracts, etc.

Despite these flawed assumptions, 21st-century "epistemic decolonisation" cannot succeed unless it is bound to and supportive of contemporary liberation struggles against inequality, racism, austerity, patriarchy, autocracy, homophobia, xenophobia, ecological damage, militarisation, impunity, corruption, media muzzling and land grabbing.

For those who research and write about Africa, this is particularly important given the continent's fraught relationship with itself and the outside world. Though Africa remains captured today by the same forces that fuelled colonialism, African activists and artists have responded by commanding revolutionary change.

Women, Equality, and Citizenship in Contemporary Africa (Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics)→

/(2020) “Women, Equality, and Citizenship in Contemporary Africa” in Nic Cheeseman (ed.) Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics. New York, New York: Oxford University Press: 1834-1856.

How Africa Can Adopt a Pan-African Migration and Development Agenda (Harvard Africa Policy Journal)→

/(2019) “How Africa Can Adopt a Pan-African Migration and Development Agenda.” Harvard Africa Policy Journal 14: 20-32.

The Struggles for Liberian Citizenship (Al Jazeera English)→

/It has been exactly one year since newly inaugurated Liberian President George Manneh Weah sparked controversy by declaring staunch support for enacting dual citizenship and repealing a constitutional "Negro clause", which prohibits non-blacks from obtaining citizenship by birth, ancestry or naturalisation.

Although the footballer-turned-president acknowledged the historical preoccupations of Liberia's settlers who fled 19th century economic servitude in the United States and the Caribbean, he claimed that upholding the "Negro clause" and prohibiting dual citizenship would impinge upon the country's 21st century post-war progress and prosperity, especially given the vital development contributions by Liberians abroad.

Yet, my research on how Liberians view citizenship in general and dual citizenship in particular - based on over 200 interviews in cities in West Africa, Europe, and North America - shows that the laws remain unchanged because objections to amendments are deeply socioeconomic in nature, and cannot be simply wished away by presidential proclamations. Liberians experience citizenship differently based on their class, gender and ethnicity, and this largely influences whether they reject or accept dual citizenship and the "Negro clause".

Between Rootedness and Rootlessness: How Sedentarist and Nomadic Metaphysics Simultaneously Challenge and Reinforce (Dual) Citizenship Claims for Liberia (Migration Studies)→

/(2018) "Between Rootedness and Rootlessness: How Sedentarist and Nomadic Metaphysics Simultaneously Challenge and Reinforce (Dual) Citizenship Claims for Liberia." Migration Studies 6 (3): 400-419.

When Foreign 'Do-Gooders' Do More Harm Than Good in Liberia (Al Jazeera English)→

/Released last week to howls of outrage, ProPublica's Unprotected is a chilling expose about a rotten and unaccountable international charity industry. In particular, it peels away the shroud of secrecy around an American NGO, More Than Me (MTM), whose white American cofounder gallivanted around the globe for years raising millions of dollars for an academy she founded in Liberia's capital, Monrovia, while her Liberian partner repeatedly raped young female recruits.

Resilience in the Face of Adversity: A Comparative Study of Migrants in Crisis Situations (ICMPD)→

/(2018) Resilience in the Face of Adversity: A Comparative Study of Migrants in Crisis Situations. Vienna, Austria: International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD).

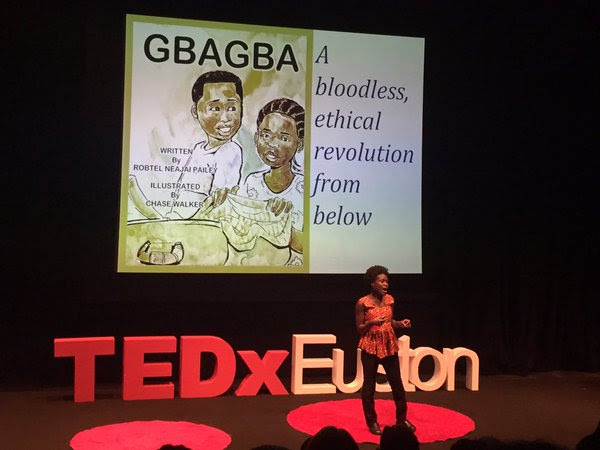

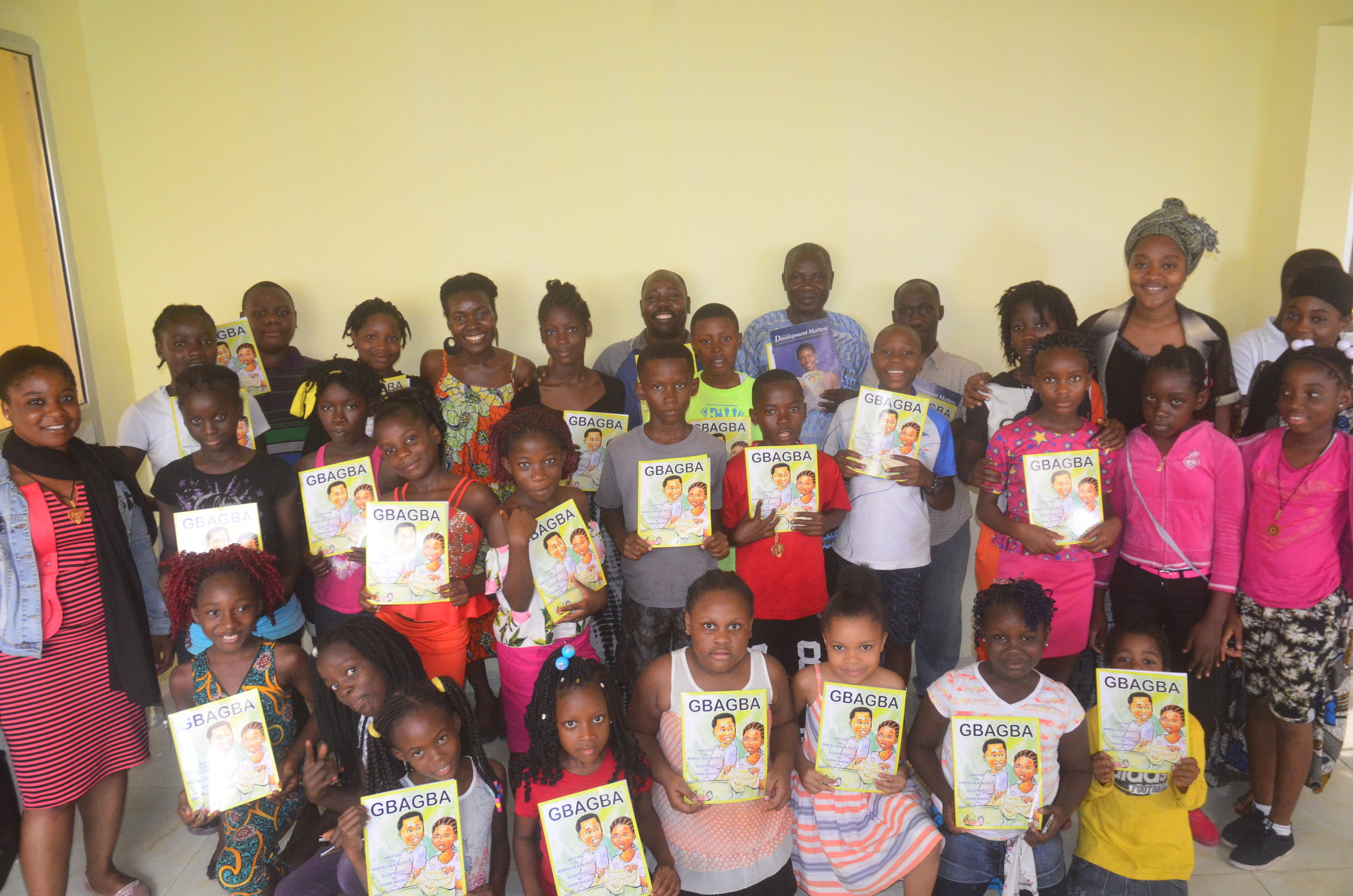

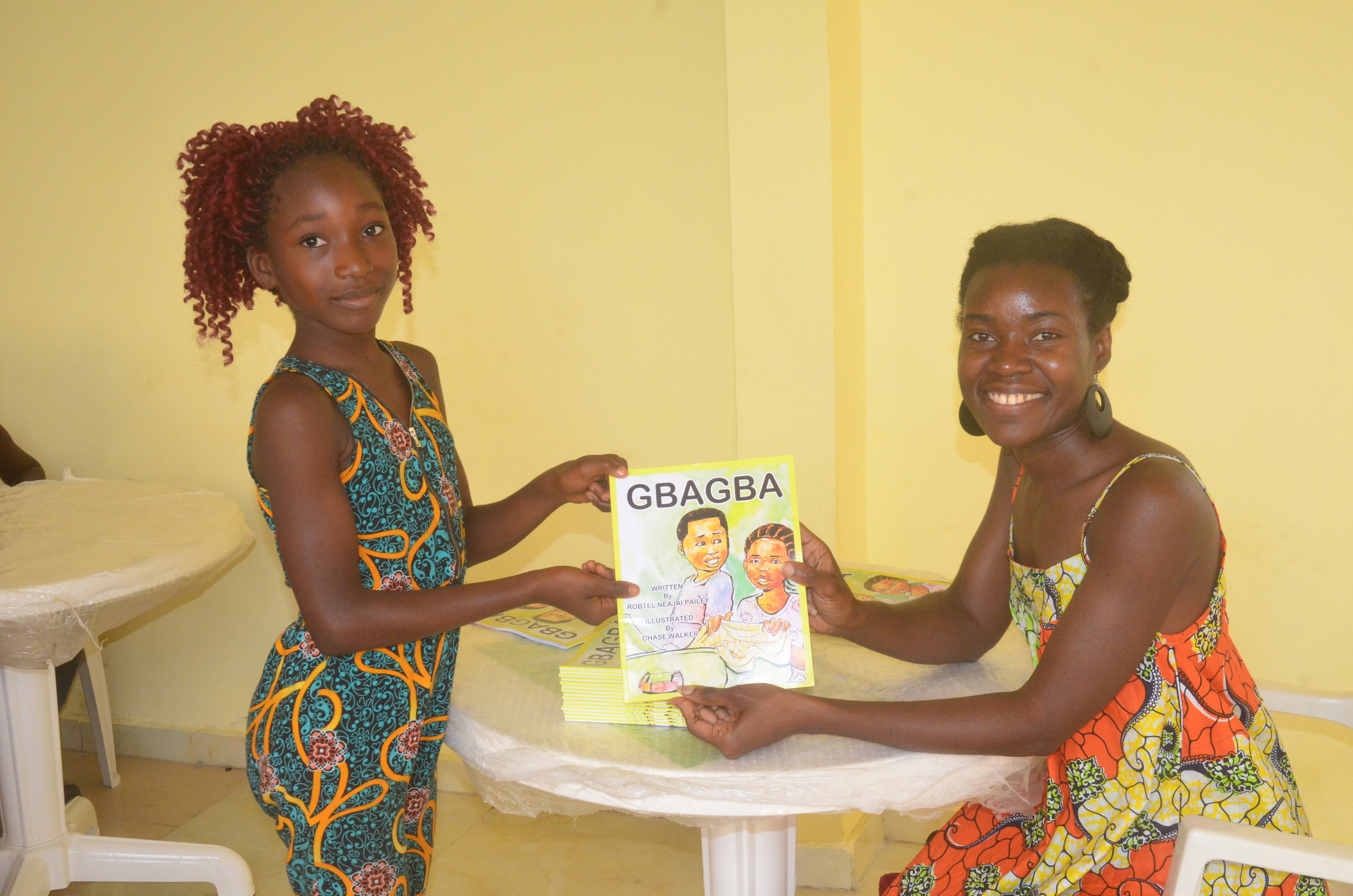

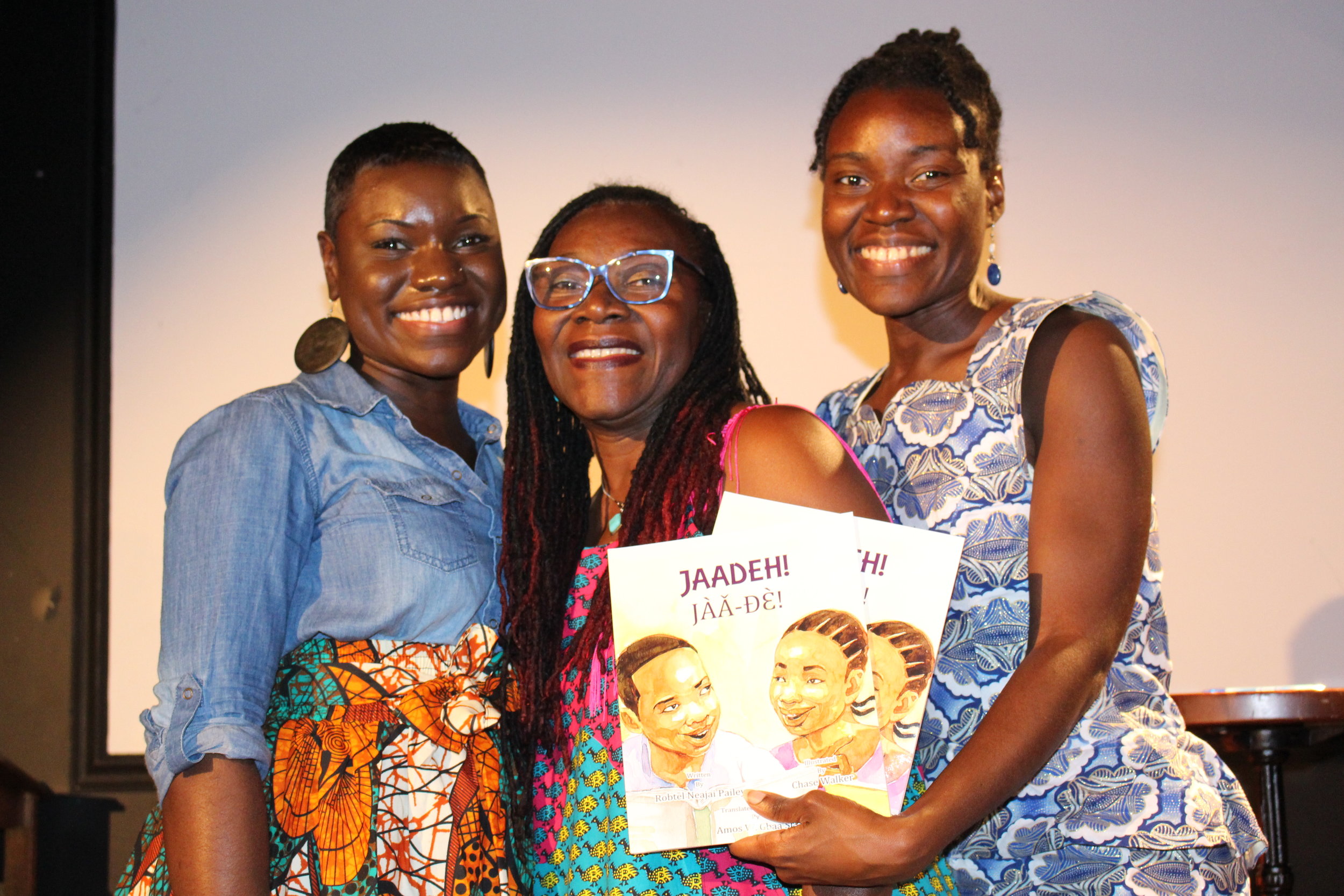

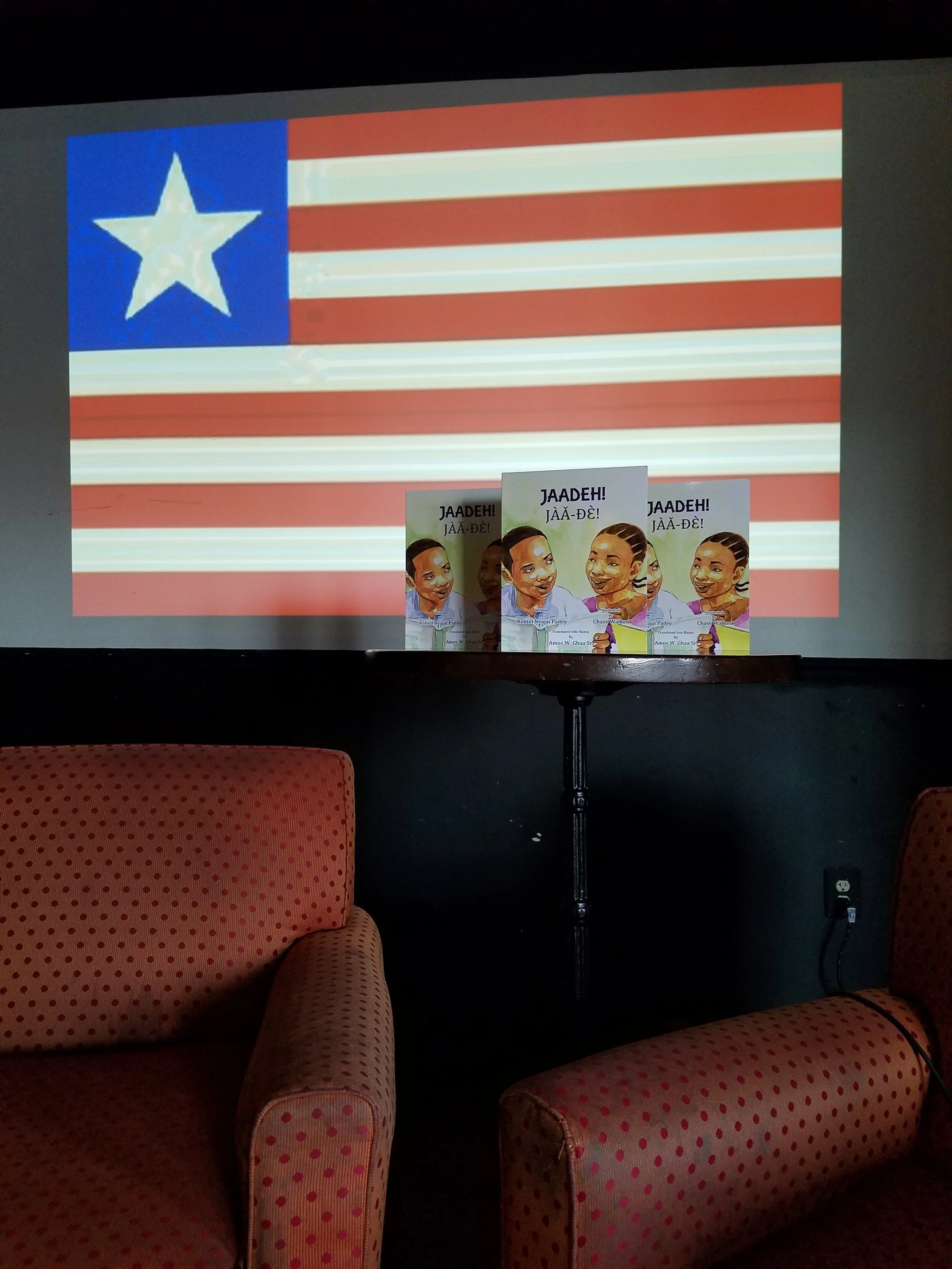

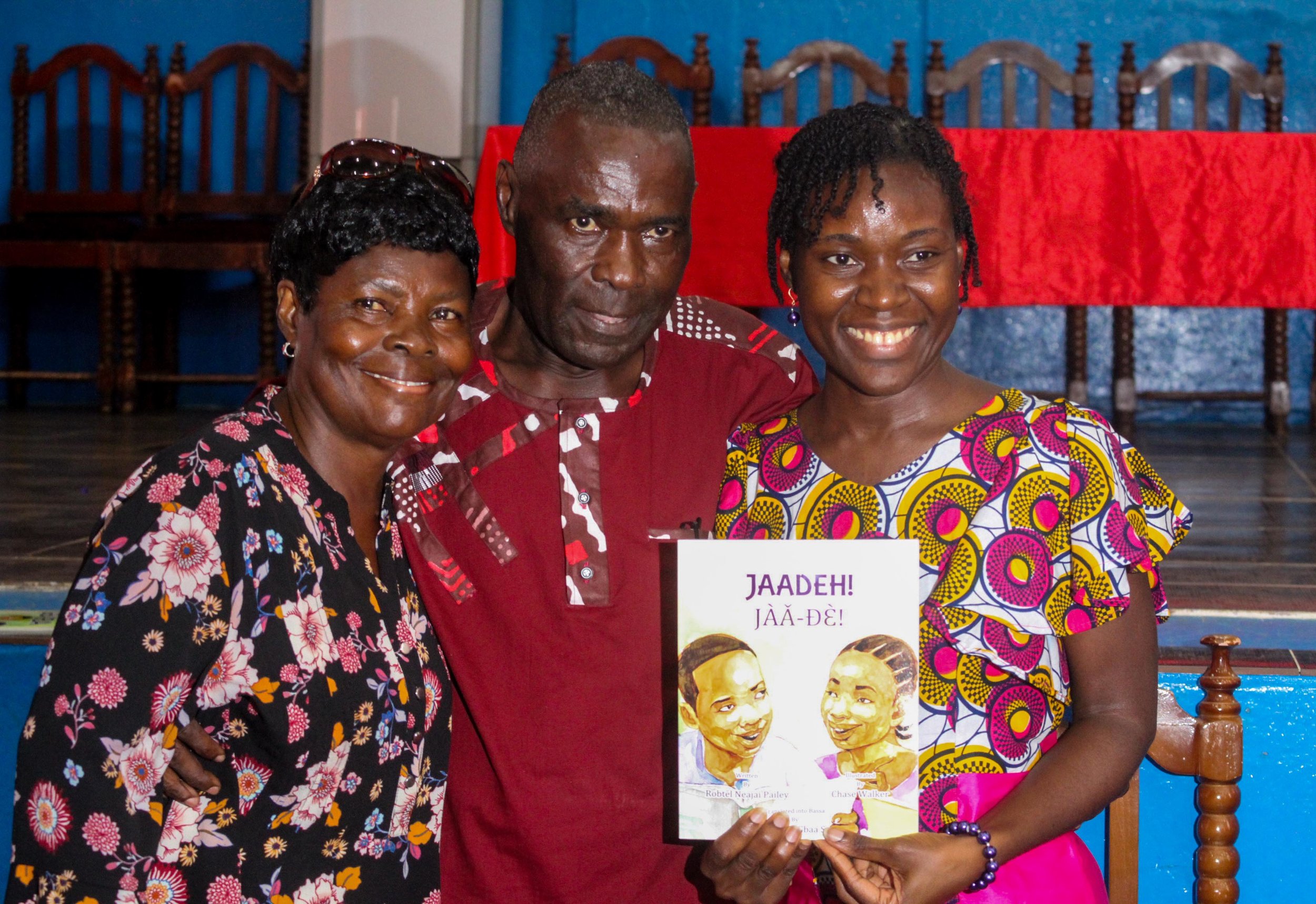

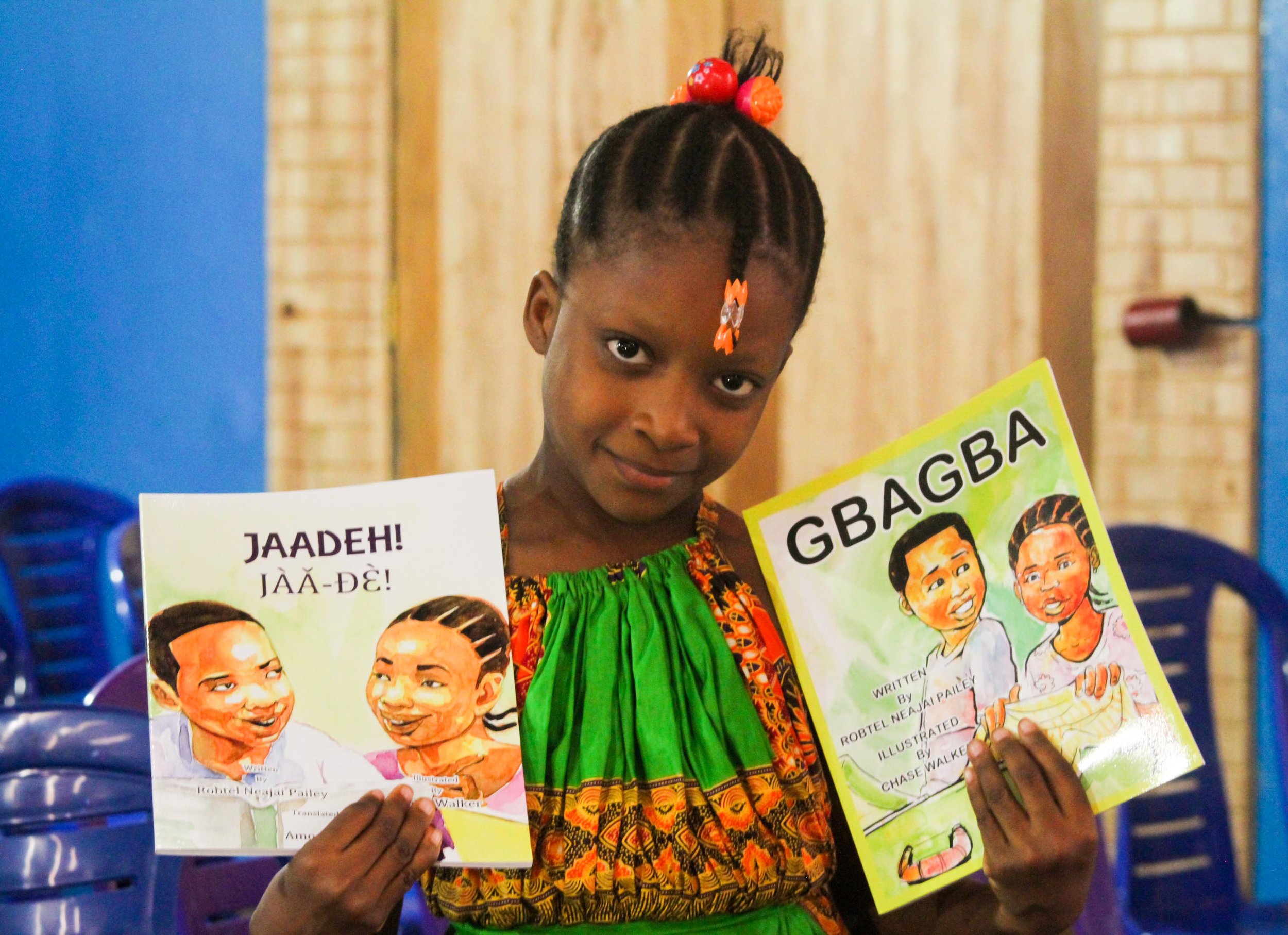

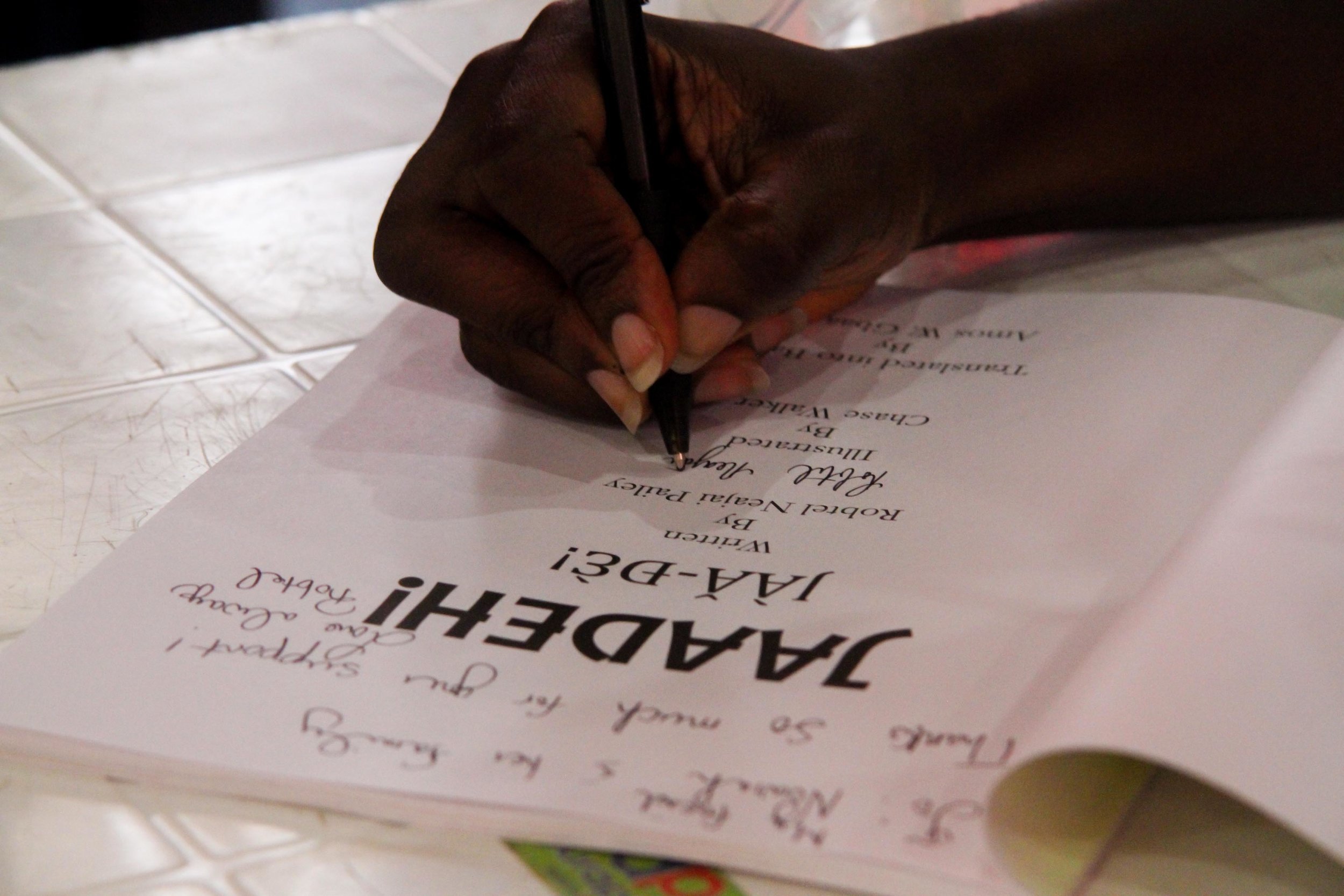

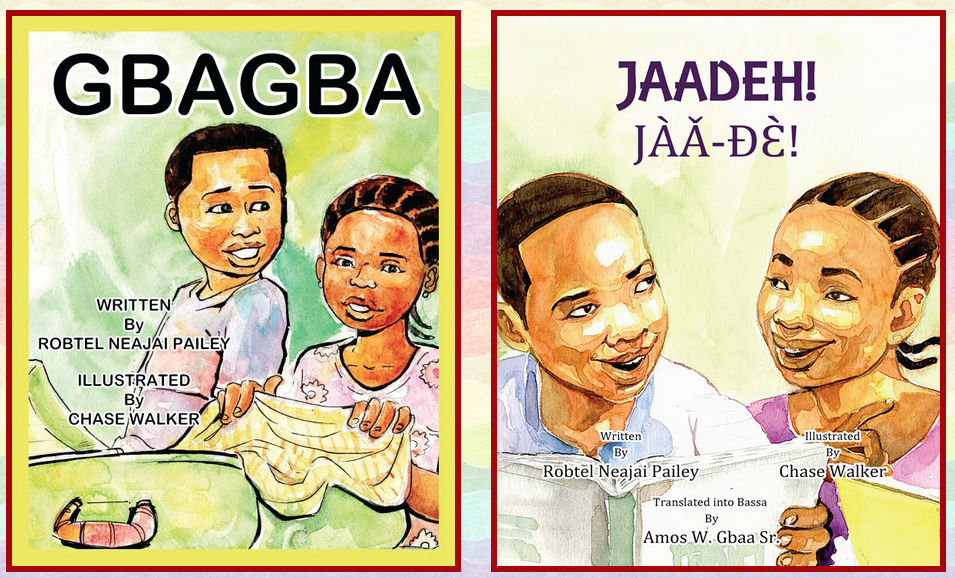

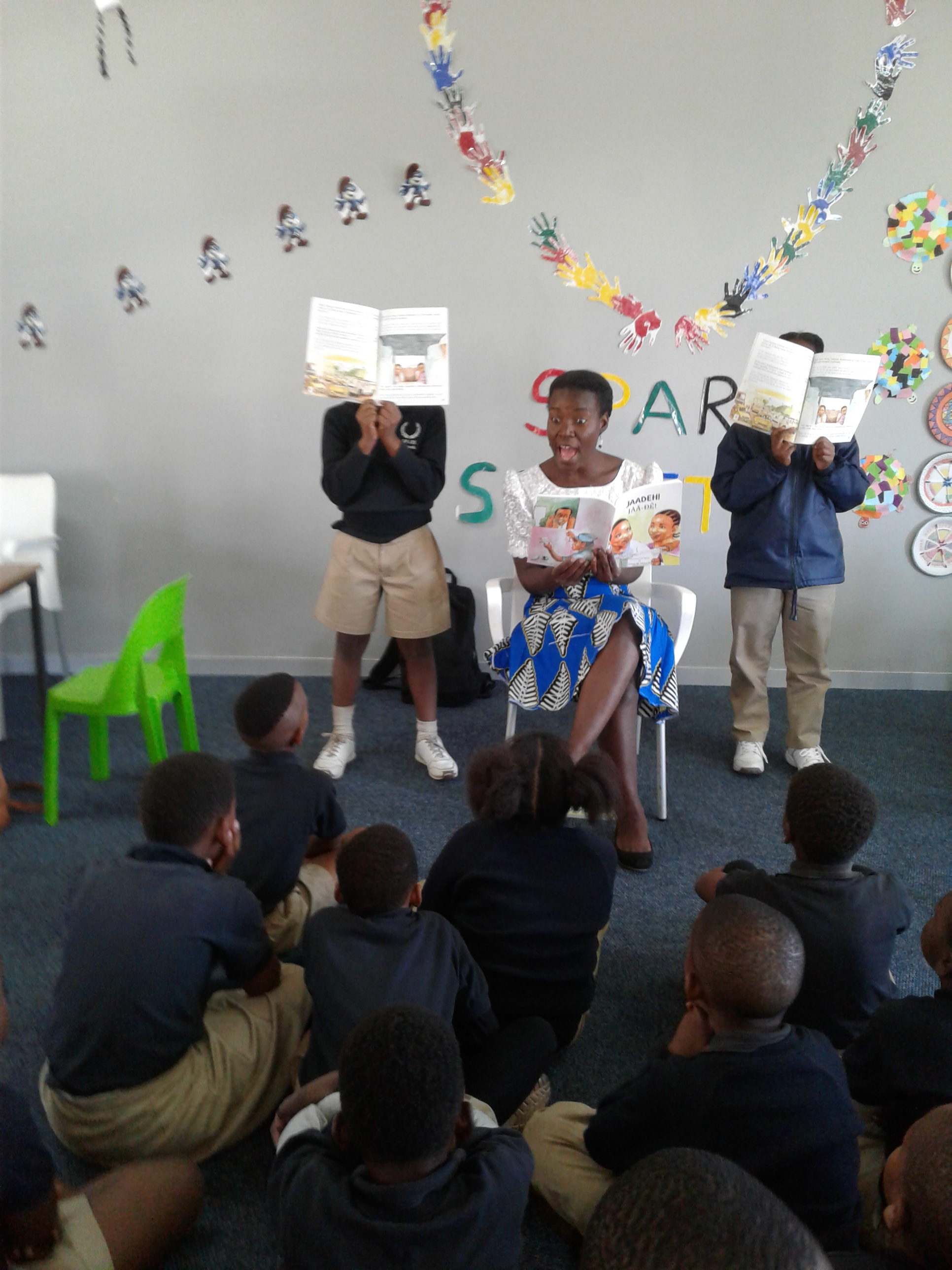

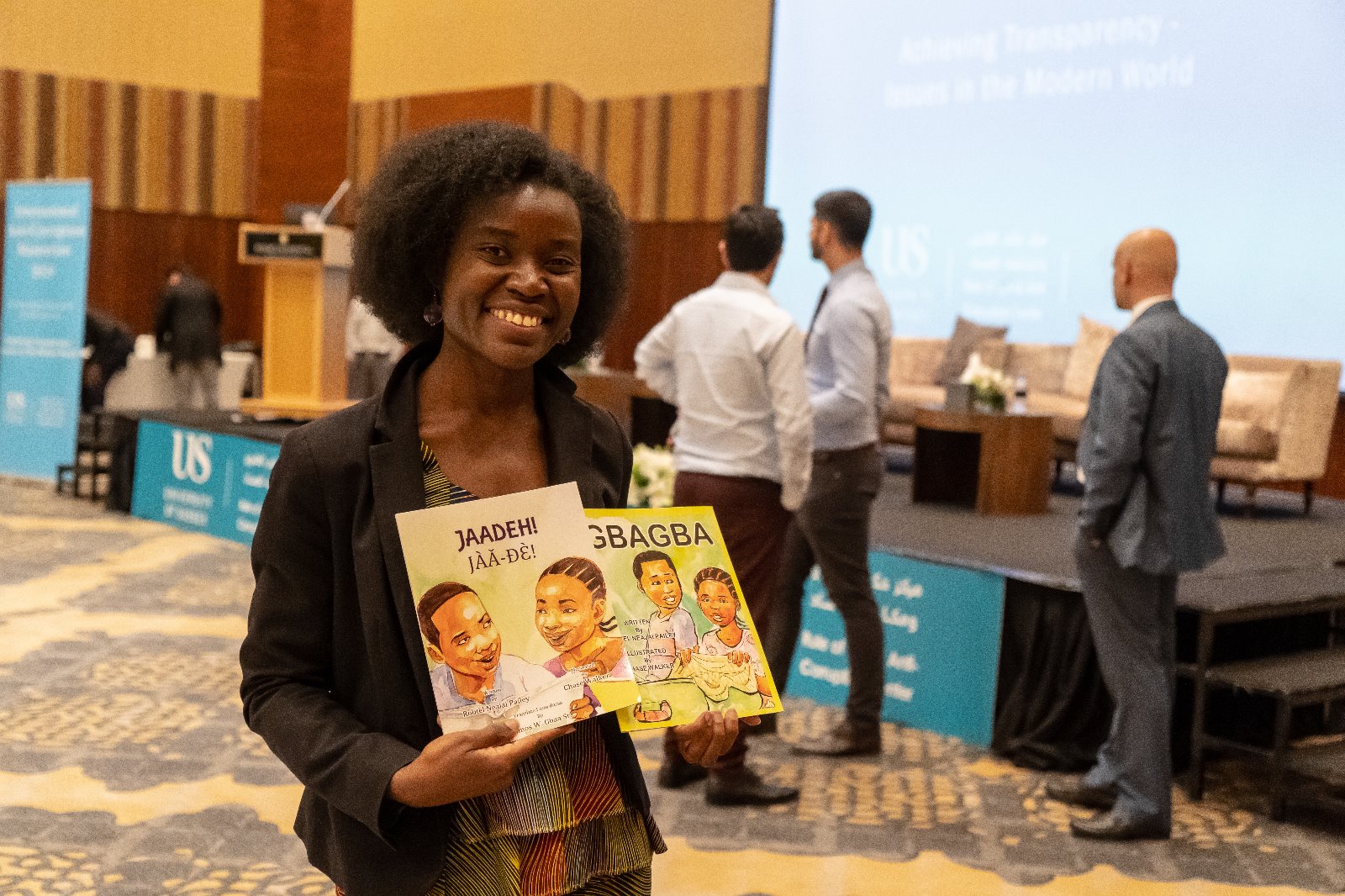

Gbagba: A Multi-media 'Revolution from Below' Teaching Children about Corruption (UNESCO blog)→

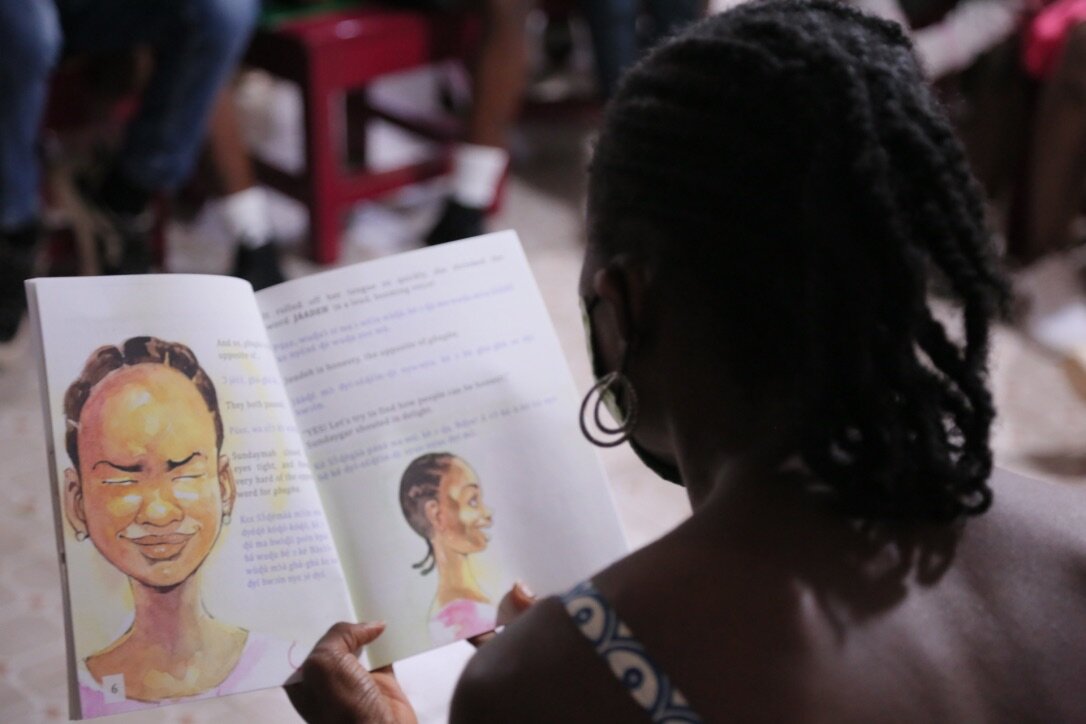

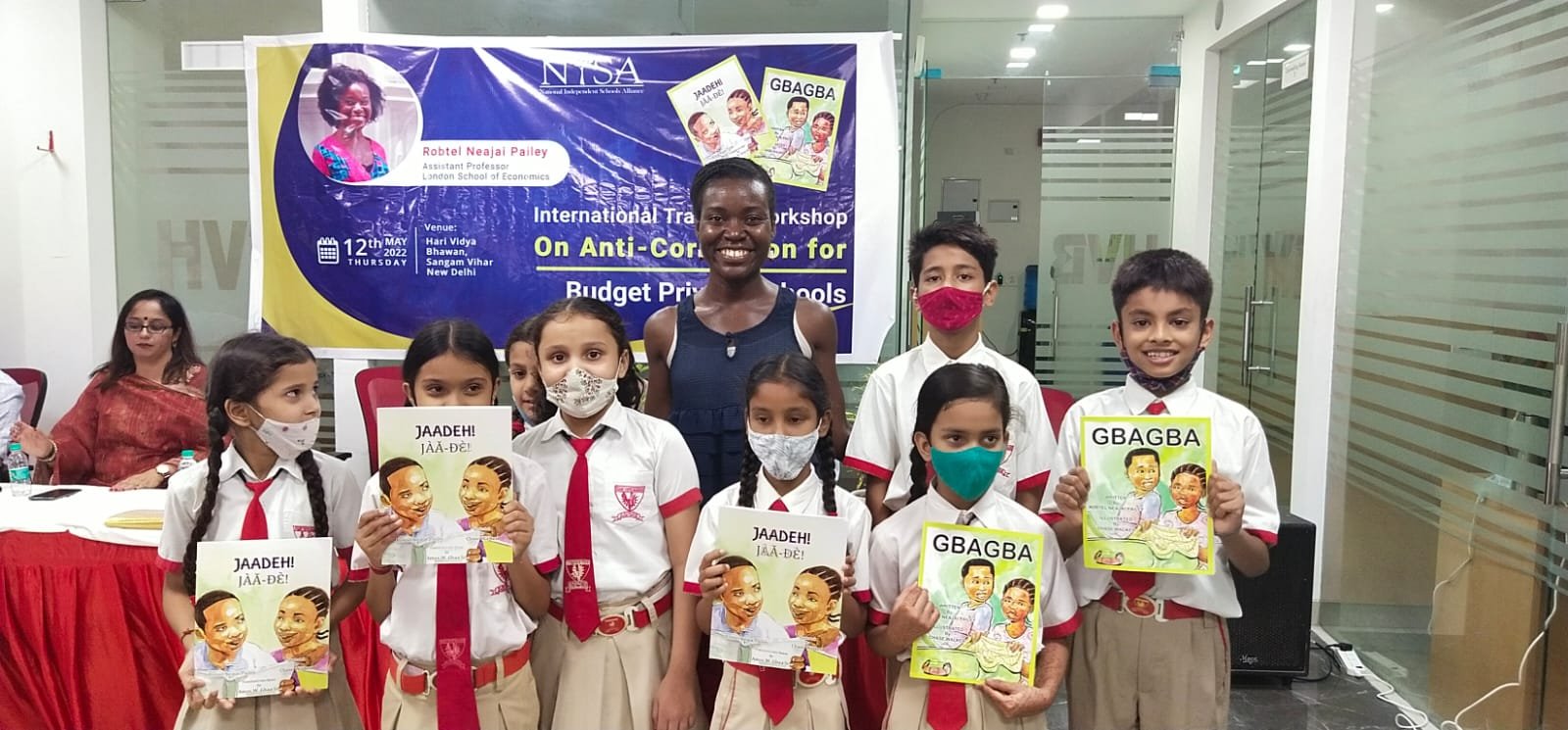

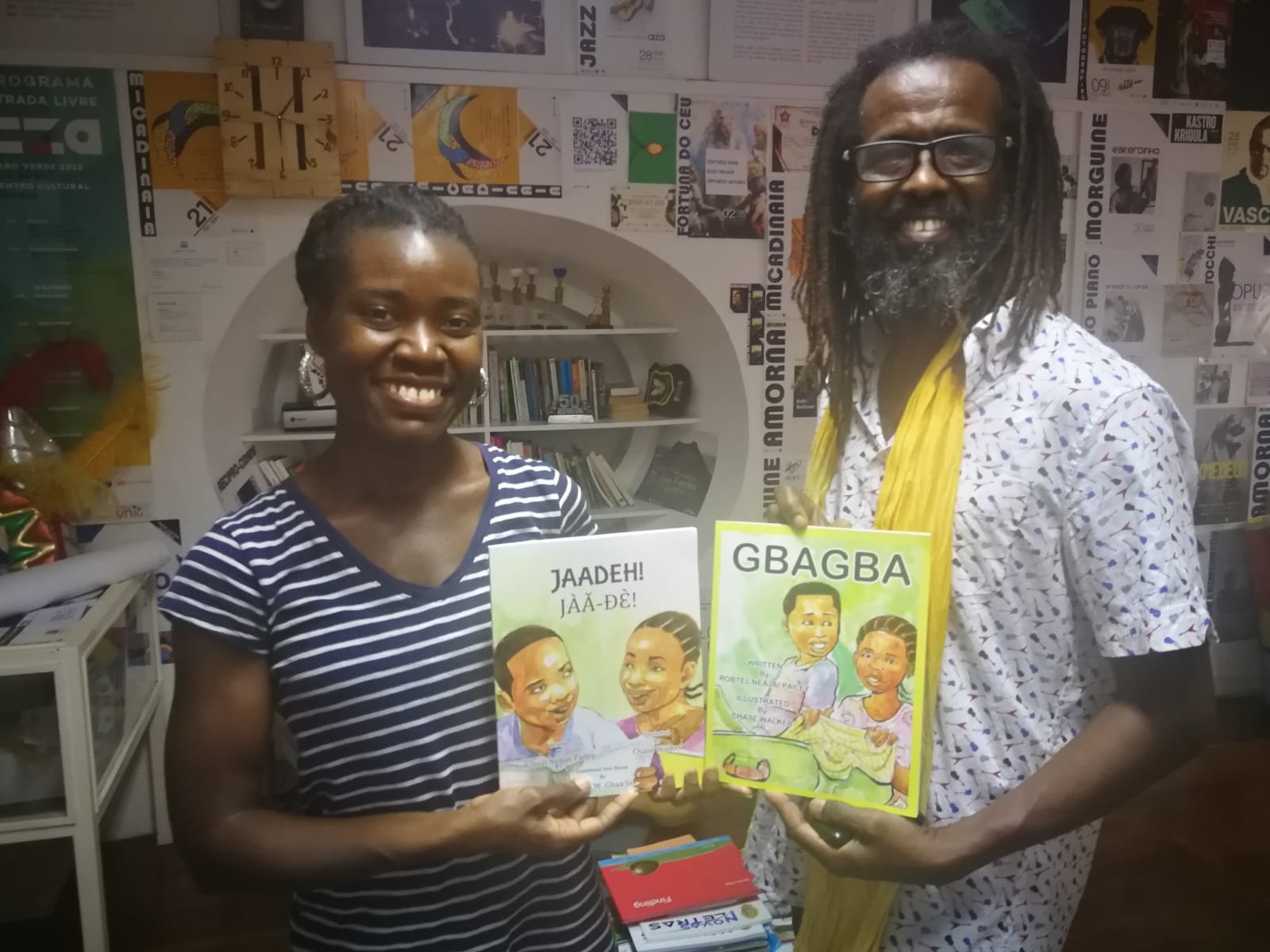

/“Police officer, what does the Liberian government need to do to encourage you to stop taking bribes?”, said a young girl from a packed audience at Monrovia City Hall Theatre in Liberia’s capital. Dressed in black and white uniform with her school’s signature red beret, the student held a microphone tightly pressed under her mouth.